BASE-UK Members Visit to Lamport - July 2023

Posted August, 15th, 2023

BASE-UK Members Visit to Lamport - July 2023

On 3rd July 2023, Members were invited to attend a visit to Agrovista's Lamport Project for an update on the work they are doing there on Blackgrass control and other trials. Niall Atkinson, BASE-UK member has provided a review of the event.

Around 70 BASE-UK Members recently enjoyed a visit to Agrovista’s trials site, Lamport AgX. The site, situated on heavy land in Northamptonshire, has become a regular visit for BASE-UK Members to view crop rotations, innovative use of crops to help with blackgrass control, many aspects of soil health, including cultivations and the use of cover crops.

Companion planting – a sustainable approach? Winter wheat and beans.

Agrovista Technical manager Mark Hemmant said: “We wanted to see if we could save on nitrogen costs and increase residual nitrogen, while introducing diversity into the rotation, and to see if there is any interaction with blackgrass, all the while maintaining a profitable output.

“Then, a few weeks ago, new Sustainable Farming Incentive options were released, including a companion cropping option on arable and horticultural land to manage nutrient use efficiency, worth £55/ha.”

Three bean seed rates were compared – none (winter wheat only), winter wheat plus 40 beans/sq m and winter wheat plus 20 beans/sq m, overlaid with four soil-applied nitrogen regimes (0kg/ha, 90kg/ha 130kg/ha + MZ28 and 180 kg/ha) and three destruction dates for the beans.

“We’ve taken the view of growing wheat as the cash crop and beans as the companion crop,” Mark said. “The new SFI option says the companion crop does not have to last the whole life of the cash crop. We looked at taking beans out early, spraying them off at T2, or taking them to harvest, whilst aiming to maximise nitrogen input.”

Observations show the no-nitrogen extreme is a non-starter, although observations do show the bean plants contribute something to the wheat crop. At the other extreme, using 180kg N/ha, beans appeared less healthy.

“Is the wheat crop too competitive, or have we made the beans lazy by applying nitrogen?” Mark asked. “We don’t yet know the answer, but we may not get a legacy effect for the next crop.”

The 90kg N/ha plot looked much better. “This suggests we might get a benefit from the beans and obtain a nitrogen saving.”

The final nitrogen regime limited soil-applied N to 130kg/ha and topped up with a slow-release foliar N, as in MZ28. “The beans in this one don’t look as lazy as the full 180kg/ha,” said Mark. “This might be the more sustainable approach.”

Oats and Beans.

The Lamport team is also investigating whether last year’s excellent results achieved by growing winter beans and winter oats together (boats) after a run of cover crop/ spring cereal sequences can be achieved using spring-sown beans and oats.

Niall Atkinson, BASE-UK Member, and trials coordinator at Lamport AgX, said: “Introducing spring boats is a natural progression given the importance of spring crops in controlling blackgrass on this site.

“The only inputs used on this plot were glyphosate pre-drilling and the oats and beans seed. Our objective is to maximise oat production – the beans are there to provide nutrition to the spring oat crops and provide a synergistic root effect. The crop looks reasonable and very clean.

“However, all our work at Lamport has shown that seedbed nutrition is important when direct-drilling spring cereals into a desiccated cover crop with no soil movement. Beans can’t supply nutrition this early so we established another plot and put 220kg of DAP down the spout, giving us 40kg of N and 102Kg of P.

“It has done a fantastic job in getting oats established earlier, but it cost about £160/ha when fertiliser prices were higher. We will be looking at replacing some or all of this nutrition with some bioscience products in the future. But we haven’t used anything else – no fungicides, no PGRs, no extra nitrogen and no herbicides, and both plots look beautiful and clean.”

Herbicide planning key to early cover crop establishment.

Choice of herbicides is becoming increasingly important the less that soil is moved, due to residue problems that can affect the establishment and performance of the following crop.

Small-seeded cover crops that are blown into the preceding standing cash crop ahead of harvest are particularly susceptible.

“It is so important to get these covers established as soon as we can to maximise the benefits. Blowing seed on using a pneumatic spreader three weeks ahead of harvest can really help”

“But the first two or three years we had very little success with this method due to the effect of residual chemistry on the cover crop seedlings. The less soil we move, the more potential issues we have. So, on this site, if we know we are going to blow on a cover before harvest, we need to plan, commented Niall.

“We don’t use sulfonylureas in the spring and limit autumn applications of diflufenican to 60g/ha, and even then, we would look to move a little soil when putting the cover crop in. We ran a straw rake through the established cover crop to help chit grassweeds too. It did a great job.”

Profitable winter wheat returns to Lamport.

Despite high grassweed pressure at Lamport, clean crops of winter wheat can be achieved, even when sown in September.

“However, you need to stick to the guidelines or risk going backwards,” said Niall. “Autumn-sown winter wheat after a run of autumn cover crop/spring cereals has looked clean and healthy, with scarcely a blackgrass head to be seen.

“We’ve also been alternating winter wheat with an autumn cover crop/spring crop with success. As part of this, we’re also looking at using wheat as the spring cash crop, which could help growers struggling to find a profitable winter or spring break crop to grow on heavy land under high blackgrass pressure.

“Many people used to grow profitable continuous wheat until they were beaten by grass weeds. We know we can deal with grass weeds in the cover crop/spring wheat rotation, so we are going a step further, looking at alternating this sequence with winter wheat, and now two cover crop/spring crop sequences followed by winter wheat.”

The alternating season plot is now in its third harvest. “Although we have not achieved the winter wheat yields we get after spring beans, perhaps 1t/ha down, but we have got 7-8t/ha of spring wheat for years on this site. If we can get that and follow up with 9-10t/ha of winter wheat, that would be quite a profitable rotation. Time will tell if we can keep it going.”

Promising alternatives to bagged fertiliser.

Innovative nutrition products and biostimulants are showing promise as cost-effective alternatives to traditional soil-applied fertiliser, with some offering significant improvements to soil heath into the bargain.

P and K

The aim of these trials is to supply crops with sufficient P and K to P meet yield and quality requirements without putting any inorganic salts onto the soil.

Chris Martin, Agrovista’s head of soil health, said: “Soil tests at Lamport show a P index of 3.1 and K at 3.3. You might therefore ask why you need these nutrients, but soil tests are not representative of what is actually available to the plant.

“Every year, growth stage-related sap or grain tests show crops are low in phosphate, mainly due to high pH and high calcium levels locking them up.

“TSP might appear a cheap solution to top up phosphate , but pound for pound it is one of the most expensive and least sustainable applications you will ever use. It is mined in African countries such as Morocco, shipped halfway round the world, turned into an expensive fertiliser then sent out to farm.

“We often spread at variable rates to get the correct indices and think we are doing a great job, but on a high pH or high Ca soil like Lamport, within weeks it’s back to rock again.

“We’ve done this as an industry for 70 years, and we keep on doing it – a maintenance dressing of 80kg/ha for a 10t/ha wheat crop currently costs around £90/ha, but it’s not working. DAP and MAP are more soluble forms of phosphate but they are still eventually locked up in these soil types. We’ve ended up building a huge bank of phosphate in the soil.”

Chris demonstrated the effects of using Phosta, a soil-applied product that releases locked-up phosphorus, making it available to plants and improving soil health.

He put MAP into a calcium solution, which quickly formed insoluble calcium phosphate, going cloudy within seconds. He then added some drops of Phosta and the liquid cleared immediately.

“Phosta costs less than £15/ha. We also add Luxor, a nutrient biostimulant that over five years of trials has outperformed TSP or DAP, to help maximise the availability of P. Putting the two together costs just under £30/ha. Our last tissue and sap tests showed phosphate was bang on; we saved £60/ha and it very much looks like we’ve done the job, which will be confirmed with a grain nutrient test at harvest.”

Potash is a similar picture at Lamport. “We have such high Ca and Mg indices that potash is only around 2% of base saturation; whereas the literature suggests it should be nearer 5%.”

The whole site received 150kg of muriate of potash supplying 90kg of K, which cost around £80/ha. A further two plots received Wholly K PGA, a foliar-applied potassium metabolite complex at T1 and T2, saving £60/ha.

“The last sap and tissue tests showed levels were spot on,” Chris said. “Overall, from a P and K point of view, we’ve saved about £130/ha, we’ve done the job and, importantly, no inorganic salts have gone into the soil, so we’re not affecting the biology. I believe we can really start changing the advice that has prevailed for the past 70 years.”

Nitrogen

The potential for stacking innovative nitrogen-replacing products to replace bagged nitrogen is also being assessed.

The control plot received 230kg/ha of ammonium nitrate through the season, while the experimental plot had 130kg/ha as urea in February, with several products applied at various points to try to make up the 100kg/ha shortfall, at a price point that matched the missing bagged N, around £100/ha.

Chris said: “Cost-wise there was no difference. We started off with a nitrification inhibitor, Instinct, with the urea to keep it in the ammonium form for longer to reduce leaching and de-nitrification. Bearing in mind how wet March was, I think that paid for itself straightaway.”

A full application of L-CBF Boost followed, which NIAB TAG trials suggest can permit a 20% reduction in total nitrogen application. A foliar endophyte product which contains nitrogen fixing bacteria and is designed to fix around 20kg/ha of N was also applied to the crop, followed with a slow-release synthetic methylated urea, between T1 and T2 to replace the last 40 kg/ha of N.

Until early June the experimental plot looked greener than the 230kg/ha AN plot but it ran out of steam. “Tissue testing suggests that we did undercook it, which is not surprising in a relatively low biologically active soil such as Lamport which will have been exacerbated by the cold, wet spring,” said Chris. “Had we applied about 160kg/ha of N at the start, I think we’d have been about right,”.

There was also very little blackgrass compared with the AN plot. “Blackgrass is an early succession plant that thrives in high bacterial sols, which are encouraged by nitrates. So the no-applied-nitrate approach, which encourages a more fungal soil that favours later succession plants like wheat, is winning hands down.

“There is food for thought here – with a little tweaking we could have had a really nice crop with significantly less nitrate going into the system. This sort of approach could change the whole way we look at crops and how we grow them.”

Effect of cultivation on herbicide performance.

A replicated blackgrass trial at Lamport is looking at the interaction between two key blackgrass herbicides, Luxinum Plus (cynmethylin) and Proclus (aclonifen) and three levels of stubble cultivation, with and without additional Avadex.

The key questions being asked are: How does cultivation – or lack of it – affect blackgrass numbers and herbicide performance? Does one herbicide perform better than the other under direct drilling? How does cultivation affect performance?

Agrovista technical manager Mark Hemmant said: “Luxinum Plus is mostly root acting but is also claimed to have an impact on seed on the surface. In previous years we had found both products to have similar activity on blackgrass, but we wondered given the seed claim whether Luxinum would be a better option under a direct drilling regime.”

Three levels of cultivation were chosen – stubble rake, disc to 3cm and disc to 8cm. All plots were sown with Weaving GD drill, and were over-sprayed post emergence with Fence + Xerton (flufenacet + ethofumesate).

“We can clearly see that moving more soil produced a lot more blackgrass,” Mark said. “This showed, in what was a dry year, leaving seed on the surface was the right thing to do, especially as we had minimum seed return after the preceding cover crop/spring cereal option.

“But, had we had moisture, would this have been right? What we do know is that the better the stale seedbed the more blackgrass you can liberate later on in the life of the crop, so it is not always the best thing to do“

Observation clearly showed the value of cultural control – herbicides alone could no longer be relied on. Indeed, cultivation alone was nearly as good as some of the herbicides, including Luxinum Plus.

“Bluntly, where we have blackgrass, we need the best chemistry and we need help from cultural controls to get the desired result,” Mark said.

“It’s been a difficult year, and Proclus has looked better here. Was the root activity of Luxinum affected in the dry autumn – is it more reliant on soil moisture? We know aclonifen is more persistent, so where we did have moisture was more active present?

“On balance both products look very similar, but in this trial Luxinum was perhaps not quite as good. But it is also clear neither are good enough on their own where we have heavy infestations of blackgrass, as at Lamport.”

Soil health improvements gather pace at Lamport.

The beneficial effects of reduced tillage and cover crops on soil organic carbon content are becoming increasingly apparent after five years of studies here at Lamport.

A series of fully replicated trials has identified a range of statistically significant changes in the biological, physical and chemical make-up of the soil, which has helped improve soil health and drive carbon sequestration.

David Purdy, a PhD candidate and John Deere’s East Anglia territory manager, who is carrying out the research, said: ”We firmly believe that good soil health starts with good photosynthesis.

“We know that healthy plants make healthy soils, not the other way round. When you have a very healthy plant in a very healthy soil, one and one don’t make two – they make a multiple of that, bringing all manner of benefits.

“So the main focus of these trials is to investigate how can we maximise a production system to get as much energy in the form of photosynthesis into our soils.”

Using cover crops in addition to cash crops is key. “By adding a cover crop we are capturing sunlight throughout the season,” David said. “An autumn cover crop/spring cropping sequence is sequestering carbon through the production cycle, whereas spring cropping on its own does not.

“As a result, soil biology has undergone a significant change over the past five years. We have seen a large increase in microbial biomass – phospho-lipid fatty acid (PLFA) production, soil respiration and rate of decomposition have all gone up statistically.

“Some went up early in the trials period, others only this year, but all the numbers are starting to correlate. We have also seen big changes in worm numbers, which has greatly improved water infiltration rates, which improves soil workability and timeliness of operations.

“We are now driving the biology in this soil pretty hard, and we’re starting to see some really significant changes in our soils in years four and five.”

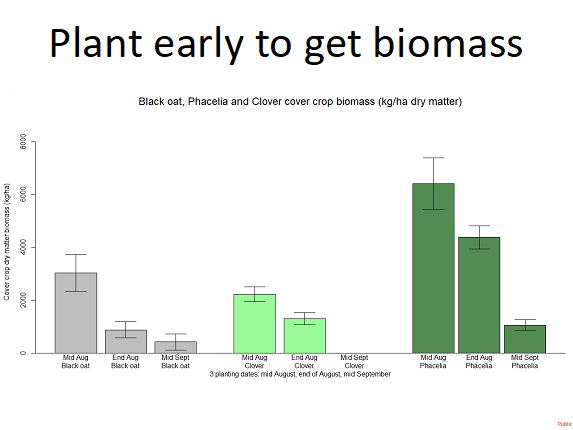

Provided cover crops are sown in good time it is possible to produce up to 6t/ha of biomass, depending on species (figure 1). About half of that is carbon.

“You have to plant covers early to drive this,” David said. “After mid-August there is a big fall-off in the three species we looked at. We will be testing others in the future.”

Figure 1:

Putting energy into soils and driving biology is delivering better physical results too. “Soil structure in particular has been a really interesting journey,” David said. “Bulk density has dropped due to the increase in soil carbon and we’ve negated the need for deep cultivations unless we damage the soil.

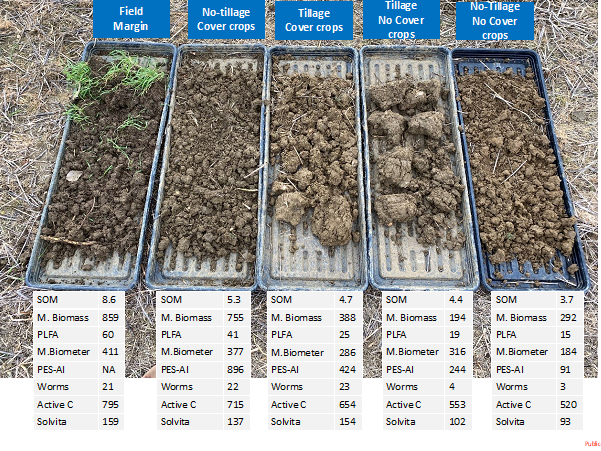

“Five years ago the soil was formed of big, lumpy blocks across these trials. After the end of year 4, we were seeing some big differences between plots (figure 2).

“The control plot, which was no tillage/no cover crops, in the fourth year started to change due to natural processes, and has started to break down more easily.

“The subsoiling plots, which have been worked to 25cm depth each season, are now big lumps of wet mass – we’ve really denatured it. So deep tillage is causing a huge degree of problems with soil structure.”

David has also studied soil chemistry extensively at different depths. “It’s a difficult one, but suffice to say our cover crop systems have stabilised electro-conductivity at between 0.4 and 0.8, increased soil nitrogen and done all sort of positive things with different elements.”

After five years the no-till/cover crop plots have significantly higher levels of soil organic matter than the other systems (figure 2), apart from the field margin, which contains 8.6% SOM.

“This shows the soil in the field is capable of carrying a lot more carbon,” David notes. “Put another way, over 50 years we’ve managed to burn off a lot of organic matter in our soils.”

Carbon opportunity.

As far as carbon goes, the field margin contained 203t/ha to a depth of up to 1m, whilst the rest of the field was well below that, indicating the potential for improvement. “There’s lots of opportunity to bury more carbon in our soils,” David said.

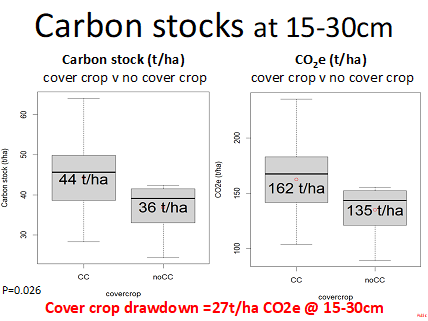

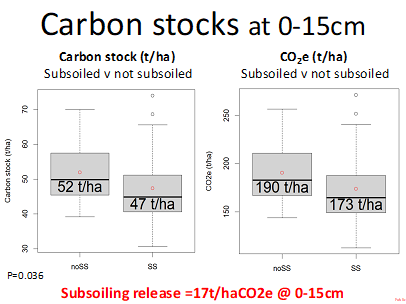

Overall, no-till cover crop treatments have significantly increased soil carbon stocks (SOM x soil bulk density x depth of core) at 15-30cm depth (figure 3) . Conversely, subsoiling treatments significantly reduced carbon stocks at 0-15cm depth (figure 4).

“We increased carbon in our no-till/cover crop plots to 44t/ha, compared with our no till/no cover plots at 36t/ha. So in five years, we’ve put 27t/ha of CO2 equivalent into this area of our soils.

“In the tillage plots, we are down to 47t/ha of carbon, compared with 52t/ha for all the no-till plots, so we’ve burnt 17t/ha of CO2 equivalent in five years, which is quite alarming – we are doing quite a lot of damage to carbon.

“Our cover crop system is very low-cost that buries carbon as well. We will continue to fine tune it and look at it from a rotational point of view, but we are now really seeing the potential of cover crops to sequester carbon, and the figures show there’s lots of opportunity to do this.”

Figure 3 and 4 below:

Target shallow loosening operations with care.

Extensive work on the silty clay loam soils at Lamport AgX has shown that shallow targeted loosening to around 15cm in combination with cover crops is sometimes necessary to alleviate compaction, but carrying out unnecessary loosening even at these depths can cause significant soil damage.

“Over the past few years at Lamport we’ve found there are times when we need to give roots a bit of help on compacted land,” said cultivations consultant Philip Wright.

In autumn 2021 roots in a black oat/phacelia/crimson clover cover crop stalled out at 10-14cm depth on a simulated turning headland plot. A loosening operation using a low-disturbance tine at 15cm stretched the soil enough to release the roots to enable deeper structuring.

“The following spring wheat crop had far more roots at depth where we loosened,” Philip said. “They appear to have followed the cover crop root channels. This alone clearly illustrated there is no need to go deep, even more so when you consider David Purdy’s findings on the damage subsoiling to 25cm can do to this soil.”

The work has continued this season in a crop of winter wheat and will be taken to yield. Similar positive findings were evident where turning compaction in the winter wheat had been loosened.

The most interesting comparison, however, was where previously uncompacted soil had been loosened – in effect, an unnecessary operation. Although winter wheat rooting was acceptable, the soil to loosened depth had consolidated (slumped).

“This visibly less porous state was worse than plots where loosening had been required, or where no actions had been taken,” Philip said. “This confirms the importance of checking your soil before incurring the cost of such operations. If soil does not need loosening, it is better left alone.”

On soils prone to slumping that have suffered shallow damage, Philip believes a shallow tine action to 10cm depth when drilling a cover can be sufficient to alleviate the problem.

“This soil very prone to running together – the silt fraction can be difficult. However, we have a bit of a dilemma. What kit can we use to structure to 10cm? It’s too shallow for a low disturbance loosener.”

The focus has been to use tine drills to establish the cover crop, to stimulate nitrogen release to help the crop establish quickly and to trigger a flush of blackgrass from near the surface so it can be destroyed later with the cover crop.

“It would appear we can also carry out a subtle enough structuring action using a tine drill, when surface conditions allow,” Philip said. “Options include a modified Weaving Sabre tine tip marketed by Bourgault Tillage Tools, which has a narrow opener which can carry out the structuring option at same time as drilling.

“We are also considering alternative modes of shallow structuring cultivation where this can be used to stimulate grass weeds outside of the commercial crop.”

Grateful thanks go to Niall Atkinson for the invitation for BASE-UK members to visit the Lamport Project once again. Also thanks to David Purdy, Philip Wright, Mark Hemmant, Chris Martin for their time and expertise and to the Agrovista team for their kind hospitality.

Recent Posts

BASE-UK FARM WALK REVIEW - JAMES BUCHER

Why regenerative farming needs to start with the soil.

BASE-UK - ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2024 - SIX INCHES OF SOIL PREVIEW

BASE-UK - ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2024 DAY 2 - HANNAH FRASER

BASE-UK - ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2024 DAY 2 - RICHARD JENNER

BASE-UK - ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2024 DAY 2 - DAVID GOODWIN

BASE-UK - ANNUAL CONFERENCE - DAY 2 - JAY FUHRER PART 2

BASE-UK - ANNUAL CONFERENCE DAY 2 - JAY FUHRER PART 1

BASE-UK - ANNUAL CONFERENCE DAY 1 - SPEAKER PANEL